cont'd...

•

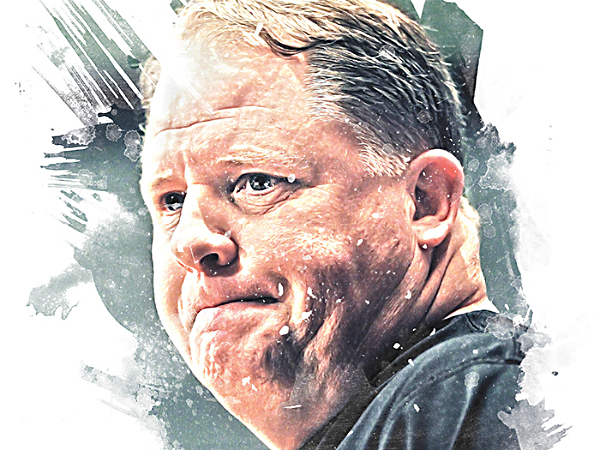

CHIP KELLY, THE THIRD of four boys, was given plenty of room in his North Manchester stomping ground: out the door early, be home when the streetlights come on at night. Football, hockey, track. School was a breeze. He was always a smart little sucker, and Manchester, once one of the biggest manufacturing cities in New England, was still a pretty sweet place to grow up.

Senior year of high school, as the quarterback of the football team, Chip would huddle his teammates under the Friday night lights at Gill Stadium, 3,000 pairs of eyes on him, then look over to Coach Leonard for the play. Coach would signal:

You call it. Because Chip made better calls than Coach.

When he was 17, Chip told Coach that’s what he was going to be, too. He wanted to coach football.

He was a walk-on at UNH, too small — at five-nine, 170 — to play much. Not long after graduation, he got hired by longtime coach Bill Bowes to oversee the running backs. One day he went into Bowes’s office and told him he wanted to coach the offensive line, those beefeaters who open up space for running backs and protect the quarterback. This was a bold request; football teams are divided up into specific areas of expertise. It was a little like a company’s HR director announcing that he should run the accounting department. Yet Bowes let him do it, and also let him change the way the line blocked, from man-to-man to zone. It was the wave of the future. Over coffee in downtown Durham, Bowes, long retired, smiles. “Chip was always ahead of the curve.” He was 25 years old.

It’s the story of most big coaches: They start running things very, very young.

But Chip’s progression was different. For almost a decade, after Bowes retired, he would run the offense under Sean McDonnell. They became very close — Sean and Chip — often hanging at Chip’s place, which generally had only freeze pops and Diet Coke in the refrigerator.

Sean trusted Chip. In fact, he trusted him so much that he gave him the keys to the kingdom, which meant that Chip would not only run Sean’s offense but could run it any way he wanted. This was back in 1999. According to an Oregon writer, a conversation they had in Sean’s office set everything that would follow in motion.

The team had had a great runner who had graduated, and Sean was at a loss over how to replace him. Together, Chip and Sean looked at the team’s depth chart — the pecking order of all the players — and Chip had a brainstorm that was striking in its simplicity: He wondered why they weren’t planning on playing the best athletes, even if they didn’t fit the schemes the team had been running. Which meant, of course, that the schemes would have to change.

Sean wondered how Chip would make that work.

“I don’t know,” he said. “But I’ll find a way.” That was the moment: He was given permission to do exactly what he wanted, to try anything.

Chip was already in the habit of spending his off-seasons visiting other schools — often on his own dime — to soak up how other teams did things. He hit the road again, and came back with the new plan, known as the spread option.

What that plan created was a sort of controlled mayhem — run at Kelly’s warp speed — in which a quarterback decides where the ball should go based on Chip moving his players around all over the field and how a defense responds. There’s nothing particularly new in that. But Kelly ramped up the speed of running plays so much, and was so good at figuring out how to get his players free of defenders, that he seemed to have devised something no one had seen before.

The offense started setting records.

Chip was a fun coach to play for, if you bought in. He worked his players hard — they had to be in great shape to play his system, and they had to make smart decisions. That hasn’t changed. He’s always pressing. And herein lies a possible answer to the NFL insider who found Chip so unrelatable personally, so limited.

“There were times I would walk by him and I knew damn well in his mind there’s, like, a film session going on, there’s plays being run,” David Ball, a receiver at UNH, once said. “You know, some people took that as him being standoffish. But he’s not.” An obsessive, yes — but not unfeeling. “He had a relationship with football.”

In 2006, Tom Coughlin, coach of the New York Giants, wanted to bring Chip to the NFL as a low-level assistant. Chip was making about $60,000; Coughlin would likely double that.

Chip said no. He’d had other offers, too. Most coaches in sports are desperate to zigzag up the career ladder, and they tend to take any better job that pops up. Not Chip. He preferred to stay right where he was, in his lab at UNH.

•

WHEN HE DID MOVE ON, he moved fast.

He was hired as Oregon’s offensive coordinator in 2007, pried loose from New Hampshire with a mandate to let it rip with his spread offense. Just two years later, he became head coach. Now he could run a whole program as he saw fit, and his restless mind — restless to take on the tired old assumptions of how football players prepare — went to work. He played loud music at practice to get his players’ juices flowing. He studied how world-class athletes trained in other sports and decreed that resting the day before a game is a very bad idea. He started monitoring his players’ diets and sleep. And he talked endlessly about attention to detail and “winning the day.” It wasn’t enough to practice hard; players had to put body and soul into maxing out their potential, like the Navy Seals Chip had come in and lecture the team.

And he became even more determined to ignore basic football tenets such as time of possession. Almost everyone believes it’s a good idea to hold the football longer than your opponent during a game. Nonsense, Chip said. The idea is to score more points. And he wants to score as fast as possible.

Chip created a team in his own lights, and he was wildly successful in his four years as head coach, going 46-7 and contending for national championships.

But there were some big challenges along the way. Oregon’s program wasn’t strong enough to recruit the best high-school players when Chip got there, which meant he had to make do with a small pool of local talent.

Before the 2010 season, there were a raft of discipline problems; incidents involving nine players had the

New York Times coming to Oregon to report on “a program run amok.” But after Kelly eventually kicked quarterback Jeremiah Masoli off the team, a sophomore who would never be good enough to play pro ball took over as QB and his troops rallied, going undefeated before losing to Auburn in the national championship game.

Observers saw a change in Chip — a new resolve not to put up with miscreants, especially if he could win without them. None of his 2010 players would be picked in the first round of the NFL draft — testament to his coaching and system and ability to adapt on the fly.

Last year, a sideline microphone at an Eagles game caught Kelly making a related point to his players:

“Culture wins football. Culture will beat scheme every day.”

Really? Was Chip actually saying that his brilliance as a play-devising maestro was less important than his troops’ esprit de corps?

Before last season, Chip’s second as Eagles coach, he cut DeSean Jackson. The wide receiver was a diva, self-obsessed, not a buy-in kind of guy, but he was also very fast, and an important piece of the puzzle. If you’re talented enough, coaches generally put up with a lot. Not Kelly. Not anymore.

This year, Chip blew up the team, cutting several veterans and signing free agents. He traded LeSean McCoy, another star, for an injured linebacker who’d played for him at Oregon. Kelly apparently didn’t like McCoy’s running style, and the contract was pricey, but another factor seems just as important: McCoy wanted to be treated like a star; that doesn’t fit the Kelly paradigm.

Those players who do buy into Kelly’s methods speak about him with great enthusiasm. I ask Brandon Graham, who changed positions in the Kelly system, if culture matters: “Oh yeah, definitely. When I think culture, I think mind-set — what do we believe in, what are we fighting for? That’s what he’s talking about. He talks about building a culture, we shouldn’t settle for average, live it every day. Live it

off the field.” Over the phone, Graham comes off not so much as a company man as someone pumping his fist in belief that the Kelly method is really a way of life.

But there’s risk in demanding so much, too. After LeSean McCoy was traded, he said of Chip to

ESPN magazine: “He wants the full control. ... You see how fast he got rid of all the good players. Especially all the good black players. He got rid of them the fastest. That’s the truth.”

Tra Thomas, a longtime player for Andy Reid who interned as a coach under Kelly for two years, tells me McCoy “was not the only one who felt that way” in the Eagles locker room. Before Kelly’s first season, receiver Riley Cooper was caught on video at a Kenny Chesney concert saying, “I will jump that fence and fight every ****** here” after he apparently wasn’t allowed to go backstage. Cooper apologized and was fined, but was later signed to a big contract extension. “Why cut everybody else who spoke out about anything,” Thomas wonders, “but accept Riley Cooper, and give him a new contract? If a black player did the same exact thing, or got caught gay-bashing, he would have been

gone.”

Those who have known Kelly for a long time say these swipes at him are absurd. Marty Scarano, Chip’s old boss at UNH, might put it best: “Chip is not a racist. He can be a bastard with everybody, regardless of religion, creed or color.”

Defenders of Kelly have noted that many new players he brought in this off-season are black, though I think that misses the real question: Can Kelly abide a certain kind of outspoken, high-profile black player, one who doesn’t align himself with the boss’s program as neatly as, say, Brandon Graham? Maybe Kelly’s problem, in other words, isn’t racial but cultural. When Chip was hired by the Eagles before the 2013 season, an NFL insider says Kelly made a lot of anxious calls looking for tips on black coaches he could hire — it seems odd that after a couple of decades traipsing the country visiting schools to learn whatever he could about football, he was apparently devoid of those connections himself.

Unsettling as all this is, a couple of amusing ironies emerge: 1. Chip Kelly once tried to recruit LeSean McCoy out of his Harrisburg high school to play for Oregon. 2. The most creative coach, the one who throws the old playbook of how to run a team out the window, is really tough, a very demanding guy — which feels pretty old-school.

Of course, Chip doesn’t seem to give a rat’s ass about any of this, either. At a press conference in late May, he was asked whether McCoy’s comments hurt him. “It doesn’t hurt me,” Kelly said. “I’m not governed by the fear of what other people say. Events don’t elicit feelings. I think beliefs elicit feelings. I understand what my beliefs are, and I know how I am.”

But what about perception?

“You start chasing perception, then you’ve got a long life ahead of you, son.”

Always competing: Chip Kelly doesn’t just answer the questions, or defend himself — he sees an opportunity to impart a lesson.

A lot of people who are supposed to know about these things — including the NFL insider who told me Chip Kelly is “socially retarded” — believe he will deliver a Super Bowl win to Philadelphia, and the proof so far is in how his methods are being scrutinized and worried over and copied and criticized. The guy who is a decade removed from a little college program is affecting the way the game is prepared for and played —

that much is true.

•

MY THIRD DAY IN NEW HAMPSHIRE in late May, when I drive to Chip Kelly’s remodeled house in Rye, park up the road, and walk back down to his place, I’m nervous. The contractor’s sign is still out front; landscaping isn’t in yet. But that SUV in the driveway suggests that someone is home.

I’m nervous not because I may have no business bothering Chip or his girlfriend, or whoever might answer the door. (Maybe it’s Dad! Doing some last-minute painting for the Chipper!)

I’m on edge for a different reason. At this point, in my own little competition with Chip of figuring out who he is, just what makes him tick, he’s winning. That’s a funny thing. He’s winning not because I haven’t figured something out about him, but because I believe I have.

I walk up the steps of his house onto a small porch. I can see into a dim living room — a long curving couch. I knock. There is movement, off of that couch.

The door opens, and Chip Kelly is dressed in a dark t-shirt and running shorts. His hair is wet, as if he’s just showered.

I tell him who I am, and that I’m writing about him. I ask him if we can talk.

“No,” Chip says. “I think my private life is my private life. It’s the way it’s always been. I come up here to get away.”

Chip’s eyes, a deep blue, examine me. His tone isn’t unfriendly. “I think people should write about the team,” he says.

Here’s what I know about him: Chip understood very early, as only the lucky among us can, just what he wanted to do. Not just coach — he wanted to attack. He wanted to find a way within a hundred-year-old game to create something new and different, something that might even change the game — something, at least, that was all his. That’s why he stayed so long in his tiny basement office down the road in Durham — because that’s exactly what he could do there. He could attack to his heart’s content, and he got very good at it.

Now, at Chip’s door, I suggest that he doesn’t have to answer personal questions. I ask him again if we can talk.

“No.”

He examines me for another moment. He doesn’t appear to be in a big hurry.

Everyone seems to wonder how a guy can move so swiftly from tiny UNH to Oregon to the NFL, and not only move so swiftly, but be so bold. No need for his team to huddle up. He’ll get rid of even very good players that he decides disrupt the mojo. And so forth.

Because he stayed right where he was until he was ready to make his move, until he knew exactly what he was doing. In fact, he has given himself no choice: Was Chip going to push the envelope at UNH and then, once he left there, dial back the aggression, merely fit in? Not a chance.

Which is why I was nervous knocking on his door — very few people figure out so exactly what they want to do and then, if they happen to bring it out into the wider world, keep right on doing it, in whatever way they see fit.

I tell Chip Kelly that I hope he has a good season. He thanks me for coming — there’s not even a hint of the impish Chip sarcasm we see at press conferences.

We shake hands. I’m done.